There she learned she suffered from postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder, one of a spectrum of mental health conditions that can occur after childbirth, spurred by hormonal and social changes. Her therapist assured her that her horrified reactions to these thoughts showed she would never act on them. With postpartum OCD, her natural desire to protect her child from bad things had just spun out of control.

And yet when news broke this past week of the Duxbury mother accused of strangling her three children, the 39-year-old Princeton resident wrote on Facebook, “It could have been me.”

The Duxbury incident has proven a double-edged sword for those pushing for more understanding of what are now called perinatal mood disorders. (“Perinatal” refers to the period before and after birth; sometimes the troubles start during pregnancy.)

Diagnosis, treatment, and public awareness of these conditions all need to improve, they say, and talking about them openly is a good first step in a society that provides little support for new parents.

But some worry the Duxbury case may stir up erroneous fears that commonplace feelings could lead to horrible ends, amid speculation the mother had developed postpartum psychosis, a very rare condition that strikes 1 or 2 of 1,000 postpartum women. The woman, Lindsay Clancy, acknowledged on social media that she had suffered from postpartum depression.

Perinatal mood disorders are common, preventable, and treatable, experts say. They rarely lead to psychosis, and even psychosis hardly ever leads to murder. Still, these conditions are serious and can cause needless suffering for the entire family.

Cases like the Duxbury incident “make the headlines and they scare the wits out of other mothers who are experiencing a difficult time but never are going to go down this path,” said Debbie Whitehill, a social worker with the Jewish Family and Children’s Service in Waltham who ran a support group for 20 years. “Becoming psychotic is incredibly rare. That’s all you hear about. You don’t hear about people who have a tough time and recover.”

Emily Hurst describes herself as normally a “very chill person.” But the anxiety she felt after bringing her newborn daughter home in 2021 left her unable to breathe and shaking uncontrollably. At first, she thought it might be a heart attack and went to the emergency room. The diagnosis: a panic attack, something new for her.

The Cambridge mother wasn’t new to postpartum mood disorders. Nine years ago, the birth of her first child sent her into a deep depression. Then 22 and just graduated from college, she and her husband had recently moved across the country to Boston. She was home alone a lot with her new son, with no career and few friends.

“I felt furious at the world, feeling I was not getting any help or relief from the already hard task of taking care of a small baby,” she said. She could feel no joy even on the brightest days.

Not until a year after her son was born did she and her family realize she needed help. Therapy and medication helped her regulate her emotions. She also benefited from joining Whitehill’s support group, aptly titled This Isn’t What I Expected. When she had her second child, she made sure to have enough support — and quickly sought help for her anxiety.

Perinatal mood disorders are estimated to occur in about one fifth of births, but many experts believe the true number is higher. These disorders include depression, anxiety, OCD, bipolar disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder — often brought on by a traumatic birth experience. And, women who have suffered from one of these disorders before pregnancy are more likely to have postpartum troubles, an important warning sign that is often overlooked. In particular those with bipolar disorder are at higher risk of postpartum psychosis, which usually starts shortly after birth.

Depression, however, must be distinguished from “baby blues,” or feelings of irritability, nervousness, and sadness that affect just about every postpartum woman in every culture, said Margaret Howard, director of women’s behavioral health at Women and Infants Hospital in Providence. It’s normal and usually dissipates in two to three weeks, she said. True depression is deeper and more persistent, and can leave a woman paralyzed in bed, crying uncontrollably, and unable to care for her baby.

The mood changes are triggered by the sudden drop-off in pregnancy hormones, said Dr. Nancy Byatt, a psychiatrist who studies perinatal depression at the UMass Chan Medical School. This dramatic fluctuation can make a person vulnerable to mood disorders, and some women are particularly sensitive to hormonal shifts.

“Hormonal pathways are inextricably linked to the pathways for depression and anxiety,” Byatt said.

These hormonal changes occur against the background of the whole-life upheaval of new parenthood, in which you lose control over your time, can’t get enough sleep, and take on terrifying responsibility for another human — and yet are often expected to return to work as if nothing had changed.

Dr. Neel Shah, chief medical officer of the Maven Clinic, a virtual clinic for family health care, said that most risk factors for perinatal mood disorders “are social in nature.”

Maven surveyed 215 patients, and found a stunning three-quarters had at least one “social need,” ranging from food to medicine to child care. More than 40 percent reported feeling lonely or isolated.

DuBois, who had postpartum OCD, had been terribly alone with her first child. Most of her friends were not even married. Being forced to return to work at eight weeks worsened her sleep deprivation and exhaustion.

On Facebook, she described those early months as a mother: “I was also working full time in Cambridge, commuting 3 hours per day, not including the drive to and from the babysitter. I was breastfeeding all night and pumping all day and washing bottles all evening.”

An obstetrical nurse, DuBois was familiar with postpartum depression. But she doesn’t recall ever being told that anxiety and OCD can also occur during this terribly vulnerable time of life.

“We set people up for failure,” DuBois told the Globe. “We do not have a society that honors and cares for postpartum families in the way they need to be.”

DuBois hid her symptoms from everyone, even her husband. “I was convinced that if I told people what I was thinking, people would call DCF and take my baby,” she said. “I was consumed by shame and guilt and fear.”

That fear, of losing custody of a child, is widespread, said Abbie Goldberg, a professor of psychology at Clark University in Worcester. This is especially true among poor families, families of color, and people who’ve had “a complex relationship with the so-called child welfare system,” she said.

“Reaching out for support can sometimes seem like a greater risk than staying silent,” Goldberg said.

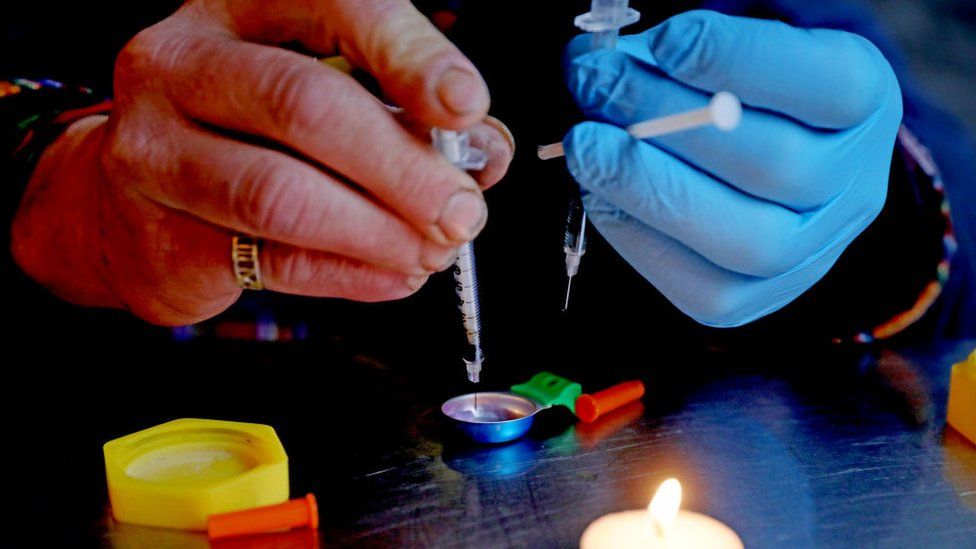

Postpartum anxiety and depression are treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy and sometimes medications, usually the same antidepressants that are prescribed in other periods of life. Only one medication, brexanolone, under the trade name Zulresso, targets the hormone pathways involved with postpartum mood disorders. Brexanolone was approved in 2019 and remains the only medication specifically for postpartum depression.

But the drug is hard to get. It requires a two-day hospital stay for a one-time 60-hour infusion. Women and Infants Hospital in Providence is the only place that offers it in New England.

“We’re getting great results and women report feeling much better very quickly … as opposed to standard treatment that can take a few weeks to take effect,” Howard said.

For Caitlyn O’Neil, it was as if brexanolone had rewired her brain.

The 35-year-old Bridgewater mother had had what she called the “perfect storm” of risk factors for a postpartum mood disorder when she had her second child in 2021: a previous miscarriage, a history of major depressive disorder, a complicated pregnancy, hemorrhaging during childbirth, and marital troubles.

“As time progressed, my mind kind of fell apart,” she said. She had thoughts of suicide, and didn’t trust herself with her children. She became so sensitive to sounds she couldn’t be in the same room with her kids.

After a stay in a psychiatric hospital, O’Neil went to Women and Infants for the two-day course of brexanolone. Within a week, she said, “I started noticing things that were different and better. The world was a different place. It still is.”

She said her relationship with her children is “amazing” these days and she and her husband, though separated, are working on their marriage.

Ashley Healy, a Concord mother, received little help for her depression, and got a firsthand view of the system’s shortcomings. After a hemorrhage during her first childbirth in 2015 nearly killed her, she went home physically depleted and feeling only “soul-crushing despair and hopelessness.” She thought her son didn’t like her.

But she didn’t know she had postpartum depression until she happened to see a note in her medical record when pregnant with her second child. The doctor’s office had not only failed to offer services or check in with her, they hadn’t even told her the reason for her distress.

Her second pregnancy was healthy, childbirth went smoothly, and she was surrounded by people afterward. Her husband had a new job that allowed him a month of paternity leave. Because the holidays were near, family members were in town. And she’d hired a part-time nanny to help out. She had no depression.

Healy’s third pregnancy, in 2019, was complicated by a rare disorder that required surgery at 30 weeks. That trauma put her at risk for postpartum mood disorder, and around five weeks after birth, she started feeling a strange rage, often a feature of postpartum depression. Only after she asked about it did her provider talk about her mood and provide a prescription for Zoloft, which helped. Still, no one checked in later to see how she was doing.

Today, Healy is among those leading the efforts to improve postpartum care. A legislative aide to state Representative James J. O’Day, she is coordinator of the Ellen Story Commission on Postpartum Depression, a permanent commission that advises the Legislature.

“There are significant issues with the screening process,” said Healy, 38, who lives in Concord. “And it’s really bad all around. It’s even worse for Black and indigenous people of color.” Healy points out that as an English-speaking white woman and a lawyer, “I have every privilege and I still was missed and not cared for.”

For help with postpartum mood disorders, contact Postpartum Support International at www.postpartum.net or call or text 800-944-4773. If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, call 988 or go to https://988lifeline.org/ to chat online.

Felice J. Freyer can be reached at felice.freyer@globe.com. Follow her on Twitter @felicejfreyer. Kay Lazar can be reached at kay.lazar@globe.com Follow her on Twitter @GlobeKayLazar.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMidWh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmJvc3Rvbmdsb2JlLmNvbS8yMDIzLzAxLzI4L21ldHJvL2l0cy1oYXJkLWJlLW5ldy1tb20tc29tZS1sb25lbHktc3RydWdnbGUtY2FuLXNwaXJhbC1pbnRvLW1lbnRhbC1pbGxuZXNzL9IBAA?oc=5

It’s hard to be a new mom. For some, a lonely struggle can spiral into mental illness. - The Boston Globe

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gray/K2DEMFBKHBHUTERD5F34XMJEG4.PNG)