Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

At the Southern Historical Collection at UNC-Chapel Hill, I found a remarkable collection of oral history interviews from the North Carolina coast during the Great Depression.

They included a seaman from Ocracoke, a country doctor from Lake Mattamuskeet, a Norwegian dredge boatman in Beaufort, a washerwoman in Elizabeth City and many more.

They ranged from the high to the low. I found an interview with the proprietor of a clothing goods store that saw the history of the Great Depression through changes in fashion and how people shopped.

But I also found an interview that showed me the hard times of the 1930s through the eyes of a young, single mother who made her living as a sex worker in a Wilmington brothel.

In this post, I would like to share excerpts from nine of those interviews. Each gives us a glimpse of life on the North Carolina coast that we don’t usually find in history books.

All of the interviews were done by the Federal Writers’ Project, which was part of what is often called President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Second New Deal.” Dating to 1935-36, the “Second New Deal” included the creation of some of the most popular legislation in U. S. history, including Social Security and rural electrification.

But the “Second New Deal” also included lesser-known programs that only lasted as long as the Great Depression. One of them was the Federal Writers’ Project, which provided jobs for unemployed historians, teachers, writers, librarians and other white-collar workers across the United States.

You can find transcripts of the Federal Writers’ Project’s oral history interviews in two collections at the Southern Historical Collection: the Federal Writers’ Project Papers and the Thadeus Farree Papers.

The ones I’m sharing here represent only a tiny fraction of the more than 1,200 Federal Writers’ Project interviews that you can read when you visit UNC Libraries. Many of them are now available online, too. Roughly a hundred of the interviews were conducted on the North Carolina coast. The rest are the stories of people who lived across the American South.

These are only nine people’s lives, but they each speak to the history of the Great Depression for countless others on the North Carolina coast and beyond. If you are like me, you will not soon forget them.

* * *

Dr. Arthur G. Harris, Fairfield

I want to begin with an excerpt of an interview with a country doctor named Arthur G. Harris. He was interviewed by W.O. Saunders, a legendary newspaper editor and publisher who worked for the Federal Writers’ Project in the late 1930s. They talked at Dr. Harris’s home in Fairfield, a remote village in Hyde County.

“This country has come upon hard times,” Dr. Harris began. “Eighty percent — yes, eighty percent — of the people in this county can’t pay for a doctor’s visit or for his medicine. Hundreds of them on WPA make barely enough to feed and clothe themselves wretchedly. Their poverty is heartbreaking.

The Works Progress Administration, or WPA) was a New Deal agency that provided public works jobs to more than 8.5 million unemployed and underemployed workers in the U.S. between 1935 and the early 1940s. In many of North Carolina’s coastal communities, few families did not have at least one individual employed by the WPA at some point during the Great Depression.

“I went into a home the other day — if you could call it a home — in which there was not a chair to sit on. I asked for a teaspoon — they didn’t have a teaspoon.

“I know of a family who, resolved to get out of debt, lived practically on cornbread for a year. No sugar, no flour, no butter, no tea, no coffee.

“I know families in which the mother, father and several children will huddle in one bed to keep from freezing to death in winter, because there are not enough beds or covering to go around. …

“Well things got so tight with me back in 1932 that I decided to leave my automobile in its garage until times got better. I have never owned an automobile since.

“Of course ,you are wondering how a country doctor can get along without an automobile. That was a question that puzzled me too until I was forced to lay my car up. But it was costing me $50 a month to run that automobile and I wasn’t getting enough out of my practice to keep up the expense of it and buy my drugs….

“I had an arrangement with a neighbor who would put his car at my disposal when I needed it. …

“It has been seven years since I laid that car up, and I have never driven it or owned an automobile since. …

“It went away piece by piece until finally there was so little left of it that two men picked up what was left of it, put it on a truck and took it to the junk pile.

“The car was in first rate condition when I laid it up, and I might have sold it for a fair price…. I thought I would resume the use of it when times got better, but times didn’t get better and neighbors, knowing the car was laid up, would run over and borrow from it whenever they needed a spare part.

“In a few years they had got all the tires, the rims, the battery, the generator, the carburetor, even the seat cushions. And then one day a neighbor came in to ask me if I’d let him have the engine block.”

* * *

A young mother, Wilmington

Another Federal Writers’ Project worker interviewed one of the many young women who felt that they had no choice but to enter the sex trade during the Great Depression. At the time, she was apparently working in Chapel Hill, but she had first worked in a brothel in a coastal seaport, Wilmington, which is why I’m including her story here. The interviewer kept her name confidential.

“That’s funny you want to know about my life,” the young woman told the man that interviewed her for the Federal Writers’ Project. “Most men don’t ask any questions except maybe, `How much?’ or “Are you clean?’ They just come and go and don’t say much.”

She had grown up in one of the state’s cotton mill villages where times had been hard and childhood was no picnic.

She asked the interviewer, “Did you ever go down in the slums of a factory town and watch the kids to see what they were doing when they weren’t working in the mills?

“Did you ever see kids not much higher than your knee prowling around at night, dumping over garbage cans trying to find a piece of bread or scrap of meat to eat?

“Did you ever see them begging a peddler for his rotten apples or fighting over what little they could get?

“Well I did. I was born and raised in a place like that, and I did my share of stringing tobacco sacks for 20 cents a day.

“Do you think I want my little boy to grow up in a place like that? Not on your life! I’ve seen too much of it!

“Do you think I’d let my little boy run around with a gang of young thieves who didn’t care about anything except stealing tires from cars and playing around at night with girls that had God knows what?

“I’ve been through it and I know what it’ll do to you. They used to come after me and try to take me out into the woods….”

To find a better childhood for her little son, the woman located a school for orphans and foster children in the North Carolina mountains for him.

From little clues in her interview, I assume that our unnamed mother was referring to the Crossnore School, which was founded by a pair of physicians, Mary Martin Sloop and her husband Eustace Sloop, in Avery County in 1913.

But she had to pay for the child to stay at the school and she couldn’t find a way to pay the fee. She had him out of wedlock. She had met the boy’s father when they were in college, but he had died in a car wreck. She later remarried, but her husband’s business went bankrupt after the Stock Marsh Crash in 1929 and he committed suicide. She had no one left to help her take care of her son.

She looked for jobs, but in the Great Depression that was incredibly difficult and harder yet for a single woman raising a child on her own.

Then things got even worse. Her child came down with meningitis and needed hospital care that she could not possibly afford. She felt the walls closing in on her, and her choices vanishing.

In her distress, she remembered a woman that she had met some time earlier. The woman, Nina, had told her that she ran a brothel in Wilmington.

“I was determined that my child was going to have the best treatment, regardless of what happened to me. I went to the telephone and called Nina in Wilmington. The next morning I received a wire from her with train fare in it.

“Well, you see that’s how I got started. I didn’t want to, and I detested the thought of it, but I was going to do anything to save my baby. I didn’t count any longer. My baby was all that mattered.

“I stayed at Nina’s about six months, and then the law came in and closed her up. I never knew what happened to her after I left, but I went from one town to another and I stopped at only the best hotels in every town….”

Many of the women she knew in the sex trade did what they had to do to survive, but of course they didn’t always make it.

“I was in a hotel at —–ville when two girls that were staying there tried to commit suicide. . .. They were both drunk on dope. In fact, they had been taking it ever since they’d been there.

“Well after they treated them both over at the hospital, they brought them back to the hotel . . .. A few days later two policemen came in and took them to jail….

“We never had much trouble with the law because they can almost always be bought off…. I thought we had to pay too much, but the cops always said they had to give the big boys their cut.”

* * *

Rev. E. C. Shue, Robersonville

Small things meant a lot during the Great Depression. Almost nothing was being built: lumber mills grew silent, brickyards were abandoned, homes that were half-built at the time of the Stock Market Crash in 1929 often remained unfinished for a decade or longer for want of money to buy lumber, nails or other construction materials.

Under those circumstances, even the building of a little Baptist church was a small miracle.

This interviewee is the Rev. E.C. Shue, a Baptist minister. The date of the interview was Jan. 18, 1939. The place is Robersonville, in Martin County. Rev. Shue was called to serve a church there in the bleakest years of the Great Depression.

“In the fall of 1932 we moved to this city. The church here had been without a pastor for two years. However, the Sunday school was attracting large crowds.

“The equipment in the church was very little, and the building itself was badly in need of repairs. It was just a one-room building to which two very small rooms had been added behind the pulpit for the Sunday school.

“The church auditorium was crossed up with wires for curtains which made a very ragged appearance. There were about a dozen different colors of glass in the windows, and there was no shrubbery on the grounds.

“I learned that several years back they had talked of building [a new church], but hard times and [the] Depression got them. All hope of getting a church were vanished.

“The Ladies Aid had some money, and some suggestion was made to use this on repairs. I saw there was absolutely no interest in building a church soon. Tobacco was very cheap [which of course was bad for tobacco farmers], and peanuts sold for 7/8ths of a cent a pound.

“Under prevailing conditions it looked like all the church could do would be to maintain one Sunday service a month.

“Seeing that all were so sure that a building could not be undertaken, I thought it was a good time to prove our faith in God and show our loyalty for His cause.

“The last week in January 1933, I showed some people some church plans and asked them to build. Some laughed and said it could not be done. All agreed it was a bad time to start a thing like that.

“Well, on March 6, the old church began to come down. When the morning papers came, they carried large headlines—ALL BANKS CLOSED. That was by order of President Roosevelt.

After a month-long run on the nation’s banks, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a national bank holiday on March 6, 1933 and closed all banks. Three days later, the U.S. Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act, which guaranteed bank deposits for the first time and restored confidence in the banking system. The country’s banks re-opened on March 13, 1933.

“Some of the folks got scared and wanted to stop the building until things got better, but it was too late. Half of the roof was off by 9 o’clock, so the work went on.

“The largest personal gift was $500 down to 5 cents. Some folks gave timber, some gave labor and some sent a hand to work a day. The pastor was put in charge of the construction. It was not long until the enthusiasm was running at high pitch.

Between the stock market crash in 1929 and the National Bank Holiday in 1933, 215 North Carolina banks failed. For long periods, some of the state’s coastal counties had no banks left in business.

“The building is stucco finish, the cement blocks being made on the grounds. My brother and I worked together, using his machinery in making the blocks.

“The ladies of the church gave us dinner and supper, and people came in great numbers to see the work go on. Some were friends and some were strangers. Salesmen coming to town heard of the work and came by to see it.

“Once started, never did the interest lag. The pastor gave his labor, planned the interior and carried the work on when the money gave out, using lumber out of the old church.

“We set out to complete the auditorium and finish the basement and Sunday school rooms later.

“But all went along together…. We were in the new church the last Sunday in August….”

* * *

John H. Bunch, Elizabeth City

In April 1939 W.O. Saunders interviewed a man named John H. Bunch at his home in Elizabeth City. Saunders identified Bunch as a “negro saw-mill hand.”

“I was born and raised on a farm down in Perquimans County. My father was a tenant farmer and a hard worker. He taught his children to work. I worked on the farm until I was 19 years old.

“Then I worked on a ground mill run by a Mr. Old…. I worked for him about three years. He paid me a dollar and 25 cents a day. That was good money in them days, but I was young and didn’t save much.

“After working for him about three years I had saved $35 and bought a horse and went to farming for myself. I farmed on shares…– I guess you’d call it about 15 acres.

“First year I raised 3 bales of cotton, 20 bags of peanuts and about 15 barrels of corn, beside my ‘taters and peas and a little garden stuff. Raised me two or three pigs, too. The landlord took one-third of the cotton, the corn and the peanuts….

“But cotton wasn’t worth but about $30 a bale, peanuts about $2.50 a bag and corn only a dollar a barrel. It took all my corn to feed the horse and the pigs.

According to Douglass Carl Abrams and Randall E. Parker in the Encyclopedia of North Carolina, crop prices fell by more than half in North Carolina between 1929 and 1933. Many farmers lost their land. Many, like Mr. Bunch, moved into towns to work in sawmills and cotton mills if they could find a job. In many of the state’s coastal counties, more than one-third of the people were on relief.

“But all years wasn’t as good as the first year. There were wet years when I hardly raised nothing and would have gone hungry if I hadn’t worked in the logwoods and for other farmers when I got caught up with my own work. I could always find work.

“But good years or bad years, there weren’t no way to get ahead on that farm. Landlord made us trade at his store. End of the year when settling up time came, I’d come in and he’d say, `John, old fellow, you got right up to the fence this year but didn’t quite get over….

“I was always in debt to that white man. And then he asked me if I was going to stay with him another year.

“If I said yes, he’d holler to his store clerk to let me a barrel of flour, a side of meat, some lard and molasses and a bolt of yellow cottons, some calico, a suit of overalls and brogan shoes.

“If I said I wasn’t going to stay, I didn’t get no provisions and he would send and take the last peck of corn that I kept for my share of the crop. He was a hard man….

“I’d been farming about two years when I married my first wife. She was a big help until she got sickly. She only lived about eight years after we were married. It was before she died that I gave up farming and moved to town so she could be near a doctor.

“There was no doctor near where we lived, and living was mighty hard too. We didn’t have much of a house, just a two-room, weather-boarded shack, not ceiled inside, with a kitchen set off from the house.

“We cooked in a fireplace. You’d be surprised what good biscuits my wife could bake in a skillet with a heavy iron cover on it.

“I came to town about 1907. It was January. Didn’t have hardly enough money to get here, but we didn’t own nothing and didn’t have much to move. Two dray loads took it all.

“I got a job at Foreman-Blades Mill where I’m still working, handling boards on the yard at a dollar and a quarter a day, working 11 hours a day.

“My wife died the August we moved here. We had four children, but two of them had died. My mother was living then and she agreed to take the two children that was living, and I broke up housekeeping.

“But after 18 months boarding, I got married again, married a cousin of my first wife.

“We rented a house and got along pretty good with my wife helping. She was always a mighty good field hand and a lot of times she could make more money than I could make, picking peas, digging ‘taters, picking cotton….”

In the 1920s, when the mill was booming, Bunch borrowed $1,000 worth of lumber from the mill owner to build a house. He had saved another $600.

“I took my $600 and bought the bricks, the shingles, nails, paint and hardware and hired my labor and built this house. It took me eight years to pay for that lumber. Interest eats you up. And then about the time I got that lumber paid for, they began to cut wages—first 50 cents a day, then another 50 cents, then another cut, until they got me down to a dollar and 40 cents a day.”

He was describing the beginning of the Great Depression. Banks closed. Unemployment rose. Businesses went bankrupt. Wages were cut, and there were mass lay-offs. People lost homes.

“Them was tight times…. If I hadn’t had this house paid for, I would have lost it. But praise the Lord, I had my house all paid for and had bought the lot side of it for a garden.

“But it was tight times. My wife toted her end, but there ain’t but so many days a woman can find work in the field…. We scrimped along somehow. Didn’t eat much meat: a chicken when we could get it, stew beef when we could get it, a mess of fish once in a while, but mostly just salt pork, sweet ‘taters, flour, cornmeal, molasses, sugar and a little butter. We never went hungry, but we had to pinch and scrape to get along….”

* * *

Capt. Otto Olsen, Beaufort

The Federal Writers’ Project interviewed Otto Olsen, a Norwegian dredge boat captain, on May 4, 1939. Capt. Olsen lived in Beaufort, but at the time he was staying on the dredge boat Callie while doing a job in New Bern. His is one of dozens of interviews in the Federal Writers’ Project Papers that sheds light on the history of immigrants on the North Carolina coast during the Great Depression.

“I was born in a little town of 14,000 inhabitants 56 years ago,” Capt. Olsen began his story. That was on a dairy farm in Norway in or about 1883.

He was one of a sizable group of Norwegian, Swedish and Dutch immigrants who settled in Beaufort in the early 1900s. Most made their livings as fishermen, sailors and boatmen.

“I did not like the farm,” Capt. Olsen went on. “My father was never at the sea, but all my uncles on both sides was at the sea and all my grandfathers on both sides as far as I know was at the sea.

“I had one great-uncle who was in the great British Navy — a captain he was, and we thought him a famous great man. So I went to sea when I was 13 years old and for only three weeks in the next seven years did I stay on the land.

“You say you want the story of my life and I am going to give it to you. But I have been so much places and seen so much things that I can’t always remember. I have been in every country in the world that has a seaport and I have been all the way around the world three times….

“I live in North Carolina now. That is, my wife, she stays here, right across from the Episcopal academy.

“She has a garden and chickens and roomers. And if you will come to see me down there sometimes I will take you for fishing.

“I stay wherever my work is, which is right here now on this dredge boat. . .. I married a woman when I was working on the dredge boat cutting the Inland Waterway. We don’t have any children of our own. But we both wanted lots [of] children, so we adopt two orphans, one boy and one girl. We send them to schools and to church . . ..

Many other couples also met when dredge boat crews dug the Intracoastal Waterway through what had been remote coastal communities. They included Douglass and Dessie Sabiston, my great-uncle and aunt.

“I am a Lutheran but there is hardly a Lutheran church over where I am now, so I go to the Episcopal Church like my wife. . .. You may hear me cuss like a son-of-a-bitch when I am working, but I always like to honor my father and mother by going to church. And all these years at the sea I say my prayers every night.

“I have had to fight some sumabitches in the fo’c’sle about my prayers and my reading. I did not go to much school, but I have read much good books and we sent the boy and girl through high school. We wanted them to have more learning than we had. It is good for them and you have much good schools in this country.

“When I was at sea whenever we made a port I went to a reading room and got me much good books. They have helped me much. I read Mark Twain and Victor Hugo most…. That Jean Valjean was a sumabitch but I liked him….

“I was shipwrecked three times: once in the Baltic Sea, and once off the coast of Siberia and once in the Gulf of Mexico. But the Gulf of Mexico was the worst. In that wreck I was the only one of 39 on board that was saved.

“I had been sailing two years on a British [ship] off the China coast when I got . . . orders to report light for a cargo of cotton for Liverpool. We weighed anchor at Shanghai, come straight down the coast, touched at Ceylon for water and coal and then crossed the tip of the Indian Ocean, on through the Red Sea and the [Suez] Canal, called again at Port Said, then through the Mediterranean and on across the Atlantic without so much as a heavy blow.

“We anchored at Hampton Roads a few days for engine repairs, cooled and watered. Then we headed out by Cape Henry and straight down the coast for Galveston.

“We were well in the Gulf when a squall covered us just out of Sabine Pass. That was the worst I have ever seen in 32 years at the sea.

“The seas were so heavy and we were so light in the hold that the propellers would not stay under the water and they raced until the shafts were broken and we was helpless adrift. The [ship] was old and as they say, ‘she couldn’t take it.’

“Her starboard slates, forward, buckled, and in less than 20 minutes we had nine feet of water in the hold and two bulkheads gone.

“Two of the lifeboats was crushed on the deck by the swells breaking over and of the two we got over [the side] one of them was swamped with all hands going down.

“The other pulled away with eleven men and they were never seen again.

“The rest of us, eight sailors, one Swede and four Portuguese negroes, made a raft from old kegs and spare planking lashed together.

“But when the raft was ready something inside me deep told me not to go—and so I am alive today. All the 12 men on that raft died in the sea and I, the thirteenth one, was saved and alive!

“But it was some son-of-a-bitch time I can tell you. The storm did not last so long and by next sunlight the sea was calm but the ship was so low in the water that a small swell would wash her main deck from stem to stern.

“I had on a lifebelt and was atop the charthouse just thinking and looking, and there was nothing to eat or drink, but all the time something inside me kept telling me I would be saved.

“It was about eight-thirty that morning when I was sighted by a tank ship. I didn’t have to make any signals as it was clear and calm and she was passing close to starboard and they could see it was a sinking ship and a man aboard. …

“I got some dry, clean clothes on the tank ship from the crew and when we made port I hobo-ed my way. I was young then and didn’t mind such things.

“I got to Galveston late one afternoon. I went to a cheap saloon and bummed a drink. I have drinked liquor and had women in almost every country in the world. But I never drank myself drunk, and that other was before I was married.

“I went from the saloon to the docks and knocked around. And who should I see but an old friend of mine—a Norwegian who had married an old schoolmate back in the homeland.

“He was working as a stevedore and making $10 a day. He told me he had a good home and he wanted me to come visit with him. I was glad to go for I was broke….

“Well I went with my friend to his house up the railroad tracks. We got there about four-thirty and we hadn’t been there long before it started getting dark. The chickens started crowing and the cows to lowing and the dogs come on the porch with their hair bristled up. Everything looked and sounded strange and quiet.

“Then the wind began to blow, then harder and harder, and the rain come down in sheets.

“We looked out the downstairs window and we saw water rising in the yard. In a little while it was over the front porch and in the front hall. We had to move upstairs.

“We carried the animals — all of them hogs, cows, dogs, chickens — up the stairs to two big rooms….

“When it was nine o’clock I stuck my hand out the window and could reach down and dip my finger in the water.

“This was the great Galveston Flood that I was living through, but we didn’t know it then. Thirteen thousand, five hundred lives were lost there.

The Great Galveston Hurricane hit the Texas coast in September 1900, drowning thousands, demolishing approximately 7,000 buildings in Galveston and leaving more than a quarter of the city’s population homeless. It was the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

“Over 20 millionaires was trapped and killed in the Exchange Building alone. And many other brick builders were brought down, but the frame buildings where the poor people lived were spared by the storm and the rich people was killed.

“And not a single whore in all the big red light district was killed, while good women was killed in churches….

“You may wonder why I am working on dredge boats after all my years at the sea. But I was getting older and decided that I had seen enough of the world for a while and wanted to stay longer in one place.

“So I got me a job in this country and in this state working on a $750,000 dredge boat that was dredging the Inland Waterway.

“The pay was good — much better than sailing on a tramp (steamer)…. And I am glad to have the job. The pay is enough for me and my wife. She owns the house and we don’t take much to live….

“I like your country and I want to stay here now. Always. There are places that I have been in other parts of the world that I think I would sometimes like to go back to, to see again, but I would always want to go back to here….

* * *

S.S. Nixon, Stumpy Point

In March of 1939, Federal Writers’ Project interviewer W.O. Saunders talked with S.S. Nixon, a 75-year-old fisherman in Stumpy Point, a remote fishing village on the mainland of Dare County.

“I was born in Engelhard, in Hyde County, in 1864, just a year before the close of the Civil War. My father was a seagoing man, the captain of his own vessel. He also owned a farm. I worked the farm until I was 22 years old.

“There was a lot of hard work and little money in farming. We couldn’t get much for the things we raised.

“In the winter of 1886, a man who had come over to Engelhard from Stumpy Point got caught by the Big Freeze and stayed with us until the ice in the creek broke up. He talked about the good fishing at Stumpy Point and begged me to come over and fish with him.

“It takes two men, sometimes more, to handle a stand of nets. I had done a little fishing, knew how to handle a boat and there wasn’t anything in farming. And so that spring I came to Stumpy Point and have lived here ever since….

“There were mighty few pound nets when I came here 52 years ago. Most of the fishing was done with gill nets. There wasn’t a gas engine in the county. We used sailboats entirely.

“We’d get out about daybreak to go to our nets and if luck was with us we’d get back before nightfall. But there were times when we struck a dead calm and had to use our wooden sails (oars!) and we’d do pretty well if we got in at 9 or 10 o’clock at night….

“But fishing was good in those days. There weren’t so many fishermen and nothing like the number of nets you see in the sounds now. We never set our nets more than 12 miles from home — often not more than 8 or 10.

“Now, with our gas boats and so much competition, we have to spread out and it is not unusual for a man to have his stand of nets 40 miles away.

“We considered a catch of 200 or 300 shad to a stand of nets a good day’s work back in the (1890s)…. Now we consider 50 or 75 shad a good day’s catch….

“But to get back to my own life: I hadn’t been here but about two years when I got married and went to fishing for myself.

“Shortly after that I built this house. Did most of the work on it myself, with some help from the neighbors. Back in those days if a man built a house or a boat, his neighbors pitched in and helped. It ain’t that way now. If you want a thing done and you need help, you hire a man and pay him.

“No I haven’t put electric lights in my house. I’ve got running water in the kitchen and we have a radio. My wife enjoys it….

“We’ve got along with oil lamps all our lives and when the power line came about a year ago I decided we wouldn’t change from oil lamps now. But most everybody went crazy for them and I know a lot who have them who can’t pay the bills when they came around. Electric lights are just another one of those things that make living more expensive.

“But it’s the automobile that has ruined things. Tbere are families here who spend more on their automobiles than they do on their living…. And this riding up and down the country and young people riding nights is breaking up homes and hurting our churches. There isn’t the interest in churches there used to be….

“When I came to this village 52 years ago, we didn’t have but three miles of road and not much of a road at that. We were cut off from the outside world by swamps and water– all travel was by sailboat.

“When we finished our spring fishing, we would pile the family on a schooner and go to Elizabeth City to lay in our supplies for the rest of the year. We never thought of making less than a week of it.

“Sometimes we would be becalmed and it would take five days to make the trip to town. But (we) enjoyed it. Nobody was in a hurry. We took life as we found it….

“But I was happy then and I am happy now. Never had much sickness, always lived within my means, never let bad habits get a hold on me — never smoked half a dozen cigarettes in my life and smoke a cigar maybe once a month, but I chew my tobacco.

“Life was hard on the farm after the Civil War, when I was a boy: worked early and late and got little for your work except the coarsest sort of clothes and mighty plain eating.

“Fishing was hard too, but there was excitement in it and you enjoyed your sleep after a hard day of it on the water. And when you got home to a hot meal, if it were nothing more than fried salt pork, cornbread and sweet potatoes, it tasted good….

“No radios, no moving pictures, but church services meant something to us and a few young folks gathered around a parlor organ in the evening, singing the old hymns by lamplight, was mighty satisfying.

“I was a grown young man before I ever saw a steamboat or a railroad train and I have lived to see the gas boat, the automobile, the electric light, the telephone, the phonograph, the radio and the flying machine. And they are cooking by electricity that comes over a little string of wire from way off yonder somewhere.

“But some things don’t change: the old truths and the old faith that men live by never change: hard work, soberness, truth, honesty and faith in God are as good for us today as they were when I first saw the light of day.

“And we live longer to enjoy our blessings. When I was a boy, a woman was old at 30 and men were crippled and bent and ready to die when they were 50 or 55.

“I haven’t many more years to live now. My time is about up, but I am not afraid to die and I have no regrets. The world has given me back in good measure about everything I put into it…. Life doesn’t owe me anything.”

* * *

Isaac O’Neal, Ocracoke

Another W.O. Saunders interview was with Isaac “Big Ike” O’Neal on Ocracoke Island, one of the Outer Banks, in the summer of 1939. Born on the island 1865, he had been a sailor, coastguardsman and merchant. After his father was crippled in an accident aboard a ship, his family struggled to get by. O’Neal only went to school for four months in his entire life and started working young.

“I remember the first money I ever made,” O’Neal remembered. “There was a clam factory here on the island. The man who owned it paid 25 cents a basket for a 5-pick basket of clams.

“I was eight years old. I took a yawl boat and went to Hatteras to get clams. Was gone two weeks and came back with 13 bushels. The man paid me 75 cents, the first money I ever made.

“And that wasn’t (real) money — the clam factory man paid off with due bills that you had to trade out at his store. I got three 25 cent due bills.

“How did I feed myself during the two weeks I was away from home? Well, I started out with 2 or 3 pones of cornbread, some sweet potatoes and a cask of water.“

“I took along my steel and flint. Clams were plentiful and two or three times I would catch me a fish and broil it over the coals after I made a fire. Slept on the beach rolled up in the sailcloth which I had taken off the yawl when I tied up for the night.

“I declare, I don’t know why a lot of us weren’t drowned in those days. About the only boats we had were yawls, the small boats we picked up from ships that were wrecked on the island. We’d boat around the sounds in those little boats in all kinds of weather. Nothing unusual to be away from home for a week or two weeks at a time.

“Yawl boats were just one of the godsends that shipwrecks sent us. We had to depend on shipwrecks for most of our luxuries. A shipwreck brought us rope, timber, hardware, cooking utensils, fuel wood and, often, food and clothing.

“I remember when the Pioneer, an Old Dominion Line steamer, came ashore and broke up. (That was in October 1889.) Most of her cargo washed out to sea, but enough came ashore for everybody on the island to lay in all sorts of supplies.

“There were hams and bacon, canned goods, coffee, yard goods, buckets, brooms, baskets and almost anything you could think of. It was a sight to see….

“When I was 14 years old, I shipped on a two-mast schooner, the Annie Farrow. She was built right here on the island. We had a heavy stand of timber on the island in those days — oak and red cedar, no pine.

“I got $8.00 a month. It was a hard life — got plenty of grub, such as it was — salt pork, beans, bread and molasses. But it was a hard life in good weather and awful in foul weather.

“The only clothes I had were the ones I stood in — a homemade wool suit that my mother had made from yarn she had carded, spun and loomed herself. I remember when we sailed out of Hatteras Inlet on that first trip I thought I’d freeze….

“The richest I ever felt in my life was when I was 19 years old. We had landed in Bangor, Maine, with a cargo of lumber. The captain paid us off and my pay was $73 cash money, the most money I had ever seen at one time in my life.”

* * *

George A. Twiddy, Elizabeth City

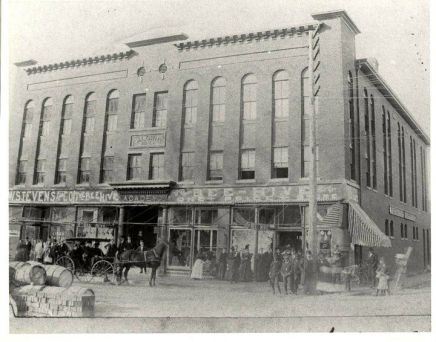

W. O. Saunders interviewed George A. Twiddy on Jan. 12, 1939. Mr. Twiddy was the senior partner at a clothing and dry goods store called Twiddy & White in Elizabeth City. I love how he sees the history of his times through the lens of fashion, clothes and the experience of shopping.

“It was the year of the total eclipse of the sun — 1900, I think it was — when I went to work for C.H. Robinson’s Fair Store. I worked mornings and afternoons before and after school and the full day on Saturdays. I was 16 years old. My pay was $1.50 a week.

“My principal job was cleaning spittoons. Spittoons were important fixtures in all stores in those days. It seemed to me that most men chewed tobacco and many women dipped snuff and were not ashamed of it. Many of our women customers used those spittoons freely.

“Shopping was different in those days. There were no automobiles. The farmer took a day off to come to town. He would leave home around daybreak, spend the greater part of the day in town, leaving town after noon and getting home around sundown. He didn’t come to town often and his shopping list contained many items.

“Often as not he brought his wife with him. Stools were provided at regular intervals in front of the counters for the convenience of patrons.

“And between stools were oversize spittoons. We didn’t call them cuspidors. There were 22 spittoons in Robinson’s Fair Store, including the spittoons in the office.

”In front of every store were hitching posts for the convenience of our rural customers. It was not unusual for a farmer to drive up with his horse and buggy, or horse and cart, at 9 o’clock in the morning and leave his horse tied until he had finished his business town at 3 or 4 o’clock that afternoon.

“At noon he would put a bundle of fodder and eight ears of corn down for his nag … and let her feed. The horse droppings were prolific and as soon as I showed up at the store in the afternoon, if I didn’t think of it first, Mr. Robinson would suggest that I should clean up after the horses.

“The streets were not paved. In places they were knee deep in mud in winter. In dry weather every passing vehicle stirred up clouds of dust. The merchants in our block had combined to build a water tank in the neighborhood from which ran a one-Inch iron pipe providing spigots on every storefront.

“With a 50 ft. length of garden hose we sprinkled the street twice a day and kept down much of the dust. Part of my job was sprinkling the street in front of the store,

“Stairs were lighted with kerosene oil lamps with bright metal reflectors. Most stores opened early mornings and closed at 9 o’clock at night. It was part of my job too to keep the lamp chimneys cleaned and polished.

“I was employed at Robinson*s less than two years when [the] Sawyer & Jones Hardware Store just across the street offered me $1.50 a week. Their offer appealed to me because they had fewer spittoons to clean and fewer hitching posts, which meant less chambermaid work for fewer horses….

“My next job was with Jones, Harper & Co., dealers in dry goods, clothing, notions, hats, boots and shoes. I was getting along.

“It wasn’t long before I was offered a better job with Owens Shoe Co. I left Owens Shoe Co. in 1907 to go with … R.J. Mitchell, the largest and busiest department store in town.

“I was a full-fledged shoe salesman then. I was with Mitchell’s for seven years, until 1914, when I engaged with my partner in the present business which we have carried on ever since.

“I’ve seen a lot of changes in merchandising and social customs in my 39 years of mercantile experience.

“Thirty or 40 years ago most women made their own dresses and undergarments or employed neighborhood dress makers. Most boys clothing and men’s trousers were homemade….

“Silk hosiery was a luxury. Sheer silk and chiffon hosiery unknown.

“There was no such thing as a woman’s custom-made hat. A woman bought a frame, so much velvet, so many yards of ribbon, certain feathers or flowers, and a milliner designed her hat to her individual notions.

“The array of such fanciful headwear in a church auditorium on a Sunday morning was a sight to behold.

“Hourglass corsets, bustles and bust forms were the height of fashion. Women even padded their coiffures with rolls of hair called ‘rats’. They wore skirts that trailed the ground and a man had to wait for a rainy day to get a glimpse of a feminine ankle.

“A man never knew what sort of figure he was courting in those days. But once matrimony admitted him to the privacy of his lady’s boudoir, what a kick he got out of seeing the lady go through the ritual of disrobing!

“. . . It took countless buttons, hooks and eyes and pins to put a woman together in those days. Even their hats were held on their heads with long stiletto-like steel or brass pins.

“The other day I was on an automobile ride, with five women in the car and I wanted a pin. There wasn’t a pin among the five of them. The modern miss releases a snap, shrugs her shoulders and drops her clothes with the nonchalance of a molting hen giving herself a shake and dropping a feather.

“A lot of water has gone under the bridge since I first went behind a counter. The merchant used to get his goods in wooden packing cases. The wooden packing case is almost a thing of the past. Almost everything today comes in paper cartons….

“It isn’t safe for a small merchant to buy in heavy packing case quantities anymore, on account of the changing styles.

“Take shoes for instance; the traveling salesmen used to come twice a year with their sample lines. We bought our fall and winter shoes in the spring, our spring and summer shoes in the fall. We can’t do that anymore.

“The manufacturers are developing new styles every few weeks. No one can tell what the trade will demand in shoes three or six months from now. The shoe salesman drops in now every 60 days. The same with women’s hats, coats and dresses.

“Even men’s shoes are subject to ever changing styles. A man’s shoe that may be the rage today may be obsolete another season. And yet I well remember when the prestige of a store was gauged by the quality of the brogan shoes it sold.

“Remember those brogans? Made of thick cowhide; stiff cowhide uppers, devoid of linings; heavy cowhide soles, not sewed on but pegged with wooden pegs. Brass tips on the toes, iron rims imbedded in the heels. Guaranteed to wear a year in barnyard manure. That was the type of shoe rural people and the working people in town generally wore 30 or 40 years ago.

“Today we have no calls for brogans and, to tell you the truth, I wouldn’t know where to buy them.

“It seems to me that the old brogan shoe was a pretty good symbol of those days, when life was hard compared with what it is today. Forty years ago – certainly 50 years ago – there wasn’t a bathtub in the whole town, no piped water in any home.

“The telephone and the electric light had not arrived. Automobiles were unthinkable, and when they began to appear early in the century they were regarded as another rich man’s toy.

“Why, I remember the sensation caused by the first barrel of gasoline that was brought to town. George W. Twiddy, who ran a small grocery store, bought a peanut roaster to be heated by gasoline.

“He had to order his gasoline from Baltimore. When his barrel of gasoline arrived, he had it carted in from the steamboat wharf and placed back of his store.

“News of the arrival of that gasoline spread like wildfire. Gasoline was thought of as a highly inflammable, explosive and dangerous article. What was Mr. Twiddy thinking of, to bring a barrel of that deadly stuff to town and set it down right in the heart of the business section? Did he want to blow the whole town up?

“The town council was hurriedly called into special session. The mayor and councilmen, with white, tense faces took immediate action. An ordinance, effective pronto, was enacted prohibiting the storage of gasoline in greater than one-gallon quantities in the city limits.

“Twiddy was ordered to remove that barrel of gasoline to the outskirts of town, where he built a shelter over it and drew out a gallon at a time as needed for his peanut roaster….

“Imperceptibly at first, but rapidly enough, the automobile revolutionized all business. Sales became smaller and more frequent.

“The farmer who used to come to town once a month or once in three or six months with a list of supplies to last him until his next trip, now runs in any day in the week and buys a pair of shoes, a suit of overalls or a plow line and goes his way.

“The stools in front of the counters have gone away with the spittoons. Nobody has time to sit and shop anymore. Spitting is taboo….

“But the automobile has otherwise effected all business. It has increased the tempo and the cost of living. With the fixed charges of his automobile, higher rents, higher taxes and other advances of modern living, the masses seem to find it increasingly difficult to meet all of their obligations.

“Darn few people seem to be able to adjust their desire for things to their ability to pay for things.

“Again, the automobile has made the larger stores and bargain days of larger city stores available to the average man or woman who formerly had to buy at home or resort to a mail order catalog.

“Every day we see cars full of people passing us by to go to Norfolk or Richmond to buy. Often as not they could do as well at home, but they enjoy the excitement of travel and the contacts with the larger city life. But down the line, the smaller country merchant is seeing carloads of his old customers going by his door, heading for ours….

“”You hear a lot of bellyaching from little businessmen these days. You’re not getting a squawk out of me; I trim my sails to the winds as they blow, and when they don’t blow for a while I put out my oars.

“I once dreamed of getting a lot of money ahead and living on Easy Street. I don’t have any such dreams anymore; I just take life as I find it, live within my means, find my social divertissements in my church and Sunday school and with the old friends who stick by us year in and year out.

“You see, business isn’t just business with us as it is with the chain stores— it’s a pleasure….”

* * *

Betty Staton, Elizabeth City

A Federal Writers’ Project interviewer named Ruth L. Riddick talked with Betty Staton at her home in Elizabeth City, N.C., in the fall of 1938. Ms. Staton was a 48-year-old African American woman, mother of four. She made her living by taking in other people’s laundry.

“Child, I have been bending this here back over washtubs and boiling pots since I was 16 or 17 years old. For the men folks that live by themselves, I charge them 50 cents if they were just hard working, but if they have good jobs I charge them a quarter more.

“I always try to figure out what they can pay according to what they can make.

“Then when I have a family’s washing, I charge $1.50 or $1.75 and if there is somebody in the family that work in grease I charge 10 cents more because that grease is mighty bad when you have to scrub and rub on it.

“I like to wash in the folks’ kitchens because then I don’t have to skimp around for wood to burn in the stove. But most folks don’t like you messing and boiling in their kitchens.

“I like to work in their kitchens because of the victuals you get to eat, too. When hard times were cramping my innards, breakfast and dinner were mighty tasty. I could save a little out and not eat it and then take home to my children.

“Hasn’t ever been no fuss about that except one time. That was a mighty penny pinching and choosey lady who was always telling me not to use too much soap powder in my washing and such as that.

“We had pork chops for dinner and I was washing dishes for her and… I saved the bones because all the meat wasn’t gnawed off of them. My children love to gnaw bones.

“Well I had a middling size bag full and she spied it. She grabbed it up and when she saw what was in it, she sure did look funny.”

Then Ms. Staton talked about how she kept her children warm during the hardest years of the Great Depression.

“It was a hard job to keep the children warm. But when I wasn’t washing, we always walked down the railroad and picked up the cinders that weren’t all burned up. Sometimes we found lumps of good coal and that burns mighty pretty when it’s mixed up with cinders.

“I [also] used to go to the backs of stores every morning early before they got to work and pick up the pieces of broken boxes that things were packed in, and they helped a lot to keep warm with.

“I wasn’t ashamed to go after they got there, but seems like when folks throw something away and then somebody comes along and picks it up, they think maybe they shouldn’t have thrown it away and then right away they want it back.

“I only have one meal a day, and that’s according to how lucky I am. Sometimes some of the neighbors that have gardens give me some greens, and I boil a pot of peas when I have them. We eat salt pork when we eat meat. I go to the fish markets and they always give me the fish they can’t sell.”

The Link LonkJuly 27, 2021 at 11:00AM

https://coastalreview.org/2021/07/hard-times-voices-from-the-great-depression-on-nc-coast/

Hard times: Voices from the Great Depression on NC coast | Coastal Review - Coastal Review Online

https://news.google.com/search?q=hard&hl=en-US&gl=US&ceid=US:en

No comments:

Post a Comment